HEXANE RESIDUES : RISKS IN FOOD AND BODY

Why both regulations and testing sensitivity need a closer look

Although hexane residues are regulated, the limits vary widely around the world. With no defined safe daily dose and outdated testing methods, these differences highlight a regulatory blind spot : how do we really know if current levels are safe?

Hexane residues are regulated, but inconsistently

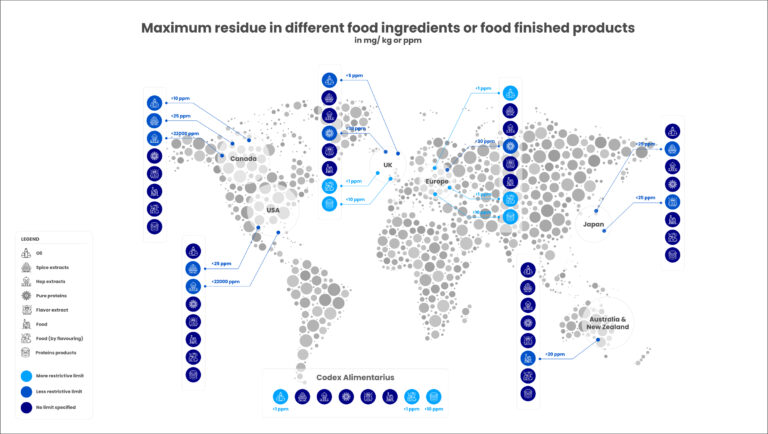

Hexane is present in various food products, yet regulatory limits differ significantly across the world. The image below illustrates how different countries set their maximum residue limits (MRLs) for hexane in food:

The Codex Alimentarius is an international collection of food standards, guidelines, and codes of practice established by the FAO and WHO to ensure food safety, quality, and fair trade globally.

The differences of accepted levels observed in the graphic raise a crucial question: “Why do different countries allow different levels of hexane in food?”

Limits vary worldwide, reflecting a lack of consensus

1. Different Approaches to Risk Assessment

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) takes a precautionary approach, setting stricter limits, whereas the USA, Canada, and Japan have higher thresholds, possibly due to industrial considerations.

2. Lack of Toxicological Studies

The U.S. EPA (2005) and EFSA (2024) have both stated that they lack sufficient data to define a safe daily ingestion dose for hexane. This means that current residue limits are not based on clear toxicological evidence, but rather on industrial feasibility and assumptions of low exposure.

3. Economic and Industrial Factors

Hexane is widely used in the vegetable oil, protein, and flavouring industries. Some countries with large food processing sectors allow higher residue limits to facilitate production and reduce costs.

4. Consumer Protection vs. Industry Needs

While some regions prioritize public health by enforcing lower hexane limits, others balance safety with economic considerations to maintain competitive food production.

Hexane’s safety is rarely reviewed, leaving outdated standards

In the European Union, food-related substances must be regularly reassessed to ensure they remain safe based on the latest scientific data.

For example, pesticides cannot be approved without a defined Tolerable Daily Intake (TDI)—a limit indicating the maximum daily exposure considered safe for humans. This value is reviewed at least every 10 years to incorporate new research and evolving scientific knowledge.

However, for hexane, no such process exists.

Despite being used in food processing, no official safe ingestion dose (TDI) has ever been established. This means that while other food-related chemicals undergo routine safety evaluations, hexane remains in a regulatory blind spot—its potential long-term effects on human health are simply not being reassessed.

According to the Codex Alimentarius, the international food safety framework: “The safety of a processing aid must be demonstrated by the supplier or user of the substance.”

Yet, in the case of hexane, this fundamental requirement is not met, leaving a significant gap in food safety regulations.

The safe daily ingestion dose is unknown, creating uncertainty

Without a peer-reviewed safe dose for ingestion, any amount of hexane could potentially be harmful, especially considering its classification as:

- Neurotoxic

- Category 2 reprotoxic (affecting fertility and development)

- Suspected endocrine disruptor (hormone interference), according to ANSES, the French national health agency

Measuring residues alone can be misleading

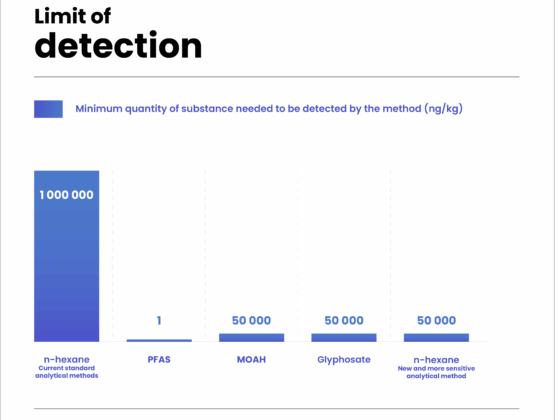

To track food and feed contamination, analytical methods must have a significantly low Limit of Detection (LOD).

The Limit of Detection (LOD) is the smallest amount of a substance that a laboratory test can reliably detect.

Imagine you’re sifting for gold in a river:

- If you use a big sieve with large holes, you’ll only catch big gold nuggets and small pieces will slip through (high LOD – less sensitive detection).

- If you use a fine mesh, you’ll catch even tiny gold flakes that were invisible before (low LOD – more sensitive detection).

💡 Why does this matter?

If the LOD is too high, small but potentially harmful amounts of hexane could go undetected. A low LOD ensures that even tiny traces of contamination can be identified, giving a more accurate picture of food safety.

Currently, The standard LOD for hexane in food is 1 mg/kg → This means hexane can only be detected if it’s present above this level.

To put this into perspective with other current chemical contaminants :

- This method is 1 million times less sensitive than method to detect PFAS.

- It is 200 to 1000 times less sensitive than methods for Glyphosate residues.

- It is 10 to 500 times less sensitive than methods for MOSH/MOAH

Why is that? It is based on a 50-year-old technique (1975) that has not been updated.

The graphic on the left shows the limit of detection for the methods used to analyze the different components.

If such outdated methods were used for Glyphosate, PFAS, or MOAH/MOSH, these contaminants would remain invisible in official reports.

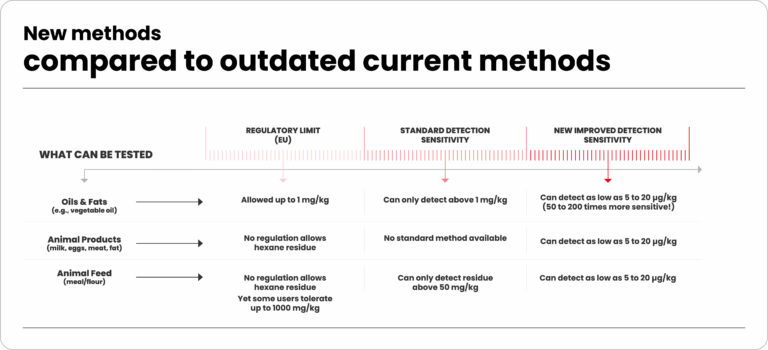

New testing methods reveal hidden risks

Advanced detection techniques have since been developed that are up to 200 times more sensitive than the current standard methods.

What does this mean?

This allows hexane to be detected at much lower levels, including in products where it was previously undetectable—such as animal products like milk, eggs, and meat.

This is significant because hexane residues in animal feed can transfer into the animals themselves and ultimately to consumers.

Testing of 51 supermarket products in 2024 found hexane in nearly half of them (24 out of 51)—including eggs, butter, and meat—despite regulations not permitting any hexane residues in animal products.

Why does this matter?

More sensitive testing shows that hexane is more present in the food chain than previously acknowledged. This underlines the need for regulatory frameworks to adapt to reflect current contamination realities.